Must-Read Short Stories from Akutagawa Ryūnosuke

November 21, 2025

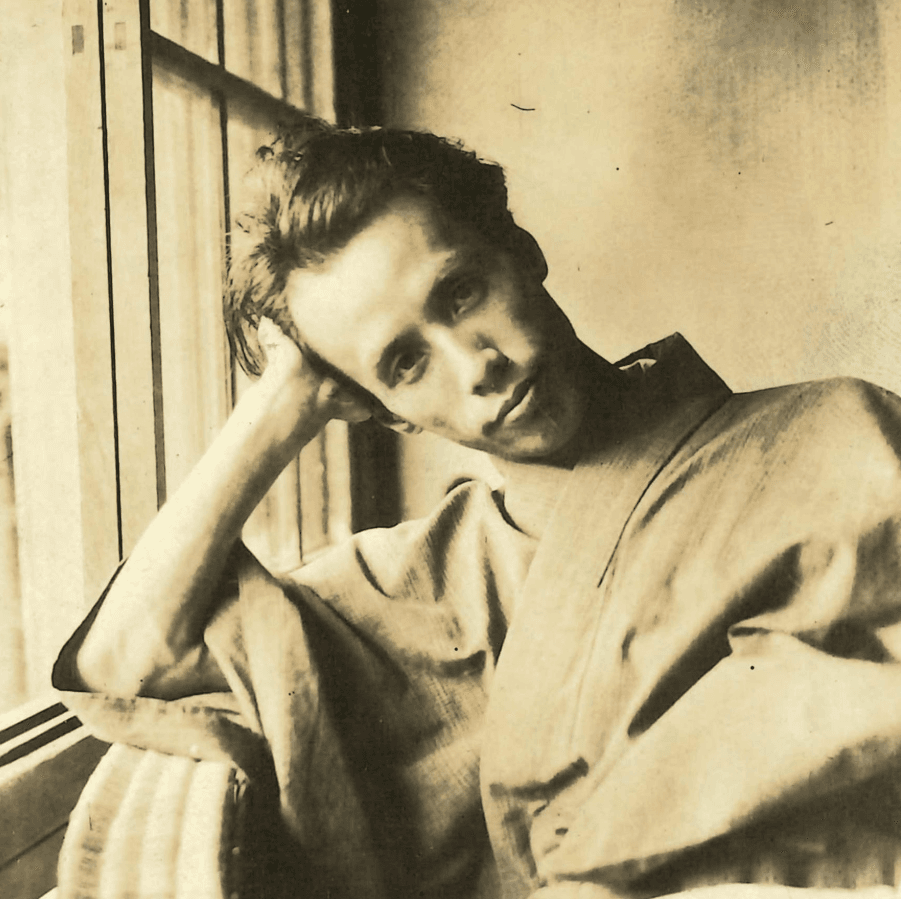

If you were asked to name the top five must-know authors of modern Japanese literature, Akutagawa Ryuunosuke’s name would certainly be near the top of that list. Along with Natsume Souseki and Dazai Osamu, he is celebrated as one of the greatest and most well-known writers of fiction the country has produced.

Writing actively from 1914 until his death in 1927, Akutagawa is known in Japan as the definitive master of the short story. His name has even become synonymous with literary excellence, as the Akutagawa Prize (芥川賞) has become one of the most prestigious literary awards in Japan.

In Japanese, the word typically used for short story is tanpen shōsetsu (短編小説), which literally means “short novel.” The issue is that what is considered a tanpen shōsetsu in Japanese spans what in English we would call a short story to works as long as a novella. So, while the Akutagawa Prize generally goes to a novella, Akutagawa himself is most recognized for his masterful short stories.

With the sheer volume of his output—over 300 works available today—his stories cover a wide range of genre, style, and mood. However, he is most remembered for a few principal works that share a distinct, unforgettable atmosphere.

The Akutagawa Style: Timeless and Mystical

What these signature works share in common is that they are primarily set in an older Japan, often long before modernity. This gives them a classic, historical flavor. They also tend to have a touch of the mystical, the grotesque, or the fantastical, which makes them stand out in the genre of literary fiction.

There is a special quality to Akutagawa’s stories that makes them stick with you. Once you read one, the story will be with you for life.

My Selection Criteria

It was hard to assemble a list of the best Akutagawa stories here because there are so many to choose from, but I made this selection with the following criteria in mind:

- Length: While Akutagawa has longer works, the stories I chose here are all quite short. You should be able to read each one in about 30 minutes at an average reading pace (it may be quicker or slower depending on your individual reading speed).

- Fame: While fame isn't the best criterion for choosing a book, it is worthwhile to consider for Japanese learners. Reading Akutagawa’s more famous works will acquaint you with stories and conventions that have proven influential for over a hundred years. You will catch literary references to these works, and you will be able to discuss them with your Japanese-speaking associates.

- Quality & Theme: All of the works I’ve selected are extremely well-written and share the particular atmosphere and tone that most people hold in their head when they think of Akutagawa—a blend of history, dark psychology, and unforgettable imagery.

Top Four Essential Short Stories

1. Rashoumon (羅生門) (1915)

Why Read It: This is arguably his most famous work, dealing with the thin line between morality and survival. Set in 12th-century Kyoto during a time of extreme decay and societal collapse, the story follows a servant who seeks shelter at one of the city’s massive gates, Rashoumon (this is just the name of the gate). While the gate itself no longer exists, it was an actual structure known from historical documents.

I don’t know how many times I have read Rashōmon, and I am sure I could still read it another dozen times without getting bored. What sucks you in is both the imagery and the psychology of the story, both of which leave us feeling like we could be there. The imagery is so masterfully written that we truly feel like we’re in medieval Kyoto with the sights, sounds, and smells. The psychology is relatable because we can picture ourselves in exactly such a predicament as the main character finds himself. How is your morality affected when your survival is on the line, and when you see others making such difficult choices? Rashoumon also sticks with you because it leaves us wondering. Readers typically finish the story full of thoughts about what may have happened to the characters after the conclusion of the story.

2. Yabu no Naka (藪の中) (1922)

Why Read It: This is a masterful exercise in unreliable narration and ambiguity. The story revolves around the death of a samurai and the assault of his wife in a bamboo grove. Akutagawa presents seven conflicting accounts of the incident—from the wife, the bandit, the samurai (through a medium), and various witnesses. Since every story contradicts the last, the reader is left in a state of deep uncertainty about what actually happened.

What I love about this story is how it first sucks in readers with the idea that, maybe if you closely analyze the accounts of each story like a detective, you can get to the bottom of the mystery and find out what really happened. The more you read over the story and compare accounts back and forth, however, the more you realize there is no definitive answer. It then makes us feel like perhaps there is a bit of truth in every account. Supposedly the author never made it clear to anyone what “really” happened in the story, and this leads us in a strange feeling of wanting more and more, but never being able to get to the bottom of it. This can lead to great discussions, as people tend to have completely different ideas about what they think was the truth behind the matter.

3. Kumo no Ito (蜘蛛の糸) (1918)

Why Read It: A brief, striking parable based on Buddhist themes of selfishness and compassion. Kandata, a notoriously wicked bandit, finds himself suffering in Hell. We get to see what happens when Buddha offers him one slim chance at salvation.

This story is amazing for two reasons. The first is that it sets up a riveting reading experience in such a short space, where we are on the edge of our seat wondering what Kandata’s ultimate fate will be, and what this tells us about salvation. The second reason is the vivid imagery that Akutagawa uses, which gives a vision of Hell unlike any that you’ve read before. You only need to read the story once for the story to stick forever in your head.

4. Hana (鼻) (1916)

Why Read It: A story about a Buddhist monk who is tormented by the fact that he has an absurdly large nose—it hangs down past his chin. The story details his efforts to hide the nose and the suffering it causes him. This work was highly praised by Natsume Souseki, helping launch Akutagawa’s literary career as a highly-respected author.

Of the four stories here, this one is perhaps the most straightforward and humorous. Despite its relatively clear message and humorous tone, however, it also speaks to something deep in our human psychology. I think this should be mandatory reading for anyone considering getting plastic surgery.

Honorable Mentions (Worth the Time)

- Torokko (トロッコ) (1922): A touching story about a young boy's journey on a hand-pushed railway cart. While this is brilliantly written and one of my favorites among Akutagawa’s works, it doesn’t contain the same unique, dark tone that Akutagawa is primarily known for. Recommended if you’re looking to read something a bit lighter in tone that still captures Akutagawa’s strong characters and vivid imagery. This story was famously praised by later literary giant Mishima Yukio was one of his favorite Akutagawa stories.

- Mikan (蜜柑) (1919): A short story that captures a moment of human connection and unexpected warmth, contrasting the cold isolation of the narrator on a train ride with a spontaneous, memorable interaction with a young girl. Again, a nice story, but very different from his most famous works. It contrasts in that it gives us a much more modern vibe (taking place on a train), and seems more like the stuff of everyday life.

- Un (運) (1917): A story focusing on a dialogue between a ceramist and a samurai discussing what it means to put one’s faith into a god. This story closely matches the style and tone of my top four picks, but readers tend to find that it does not carry the same punch as his other stories. Recommended if you have read the top four picks but feel like you want another story that captures the same historical atmosphere from olden Japan.

- Majutsu (魔術) (1920): A tale focused on a narrator who seeks to learn magic from an Indian magician he becomes acquainted with. I would recommend this story to any of those who have maybe tried reading Akutagawa’s other stories but found them too difficult. This is certainly the most easy-to-understand story on this list, but it didn’t make the top recommendations as I personally didn’t feel that the themes explored are quite as deep or impactful.

So there you have it. You don't need to commit to a 400-page novel to engage with literary genius. These short stories are the perfect way to spend a half-hour reading something foundational and deeply memorable. Pick one, and see why Akutagawa is still celebrated a century later.